2025 -- a quest for new engines of growth in the US and other advanced economies; policy instead should focus on demographic challenges

US quest for new engines of growth risks over-focus on "easy" fixes -- pushing adjustment abroad and/or relying on tech bros; it is time to acknowledge aging demographics and adjust domestic policies.

We ended 2024 in an awkward situation where:

the Fed’s rate cut cycle looked tenuous based on current trends and in need of reversing course;

fiscal stimulus (still the dominant force relative to monetary policy) increased in Q3 (headed into the US election) and Q4 (pushing out current Administration spending priorities ahead of the presidential transition);

Q4 US GDP growth accelerated per the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow measure; and

geopolitical instability was rising globally.

So far January has seen major stress on advanced economy government bond markets. Later this month, the US will get a major political and policy shift with a new Administration. Other advanced economies also appear to be making major political and policy shifts. We also seem to be in a world where the US is trying to eat other countries’ lunch. How to understand these developments? This piece offers zooms out and some big picture interpretations and reflections.

The #1 thing to understand in 2025 is that advanced economies are in search for new sources of economic growth. But most public policy still ignores the elephant in the room. Societies must openly discuss and begin to address growing demographic challenges. Aging demographics are like gravity, inescapable; but we can change our domestic policies and foster a more orderly adjustment.

Population growth — including immigration — and deficit spending have been the main drivers of US economic growth. Both of these sources of US economic growth are running out of steam. The story is as bad or worse in other advanced economies and China. Generational inequality is becoming a core structural economic and social problem.

Working age people understandably want to advocate for higher wages; older people understandably dislike inflation. A discussion must be had and a balance struck. If working age people’s lives are not made more livable, US demographics will continue to worsen and so may political disharmony.

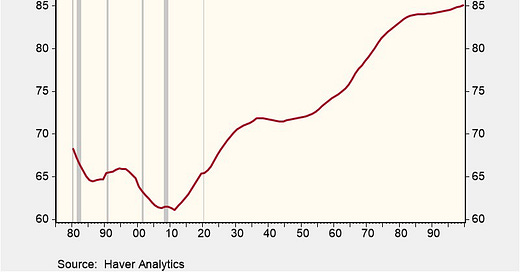

The US dependency ratio from 1980 to 2090 — children plus over 65 divided by working age population — illustrate both current and future issues.

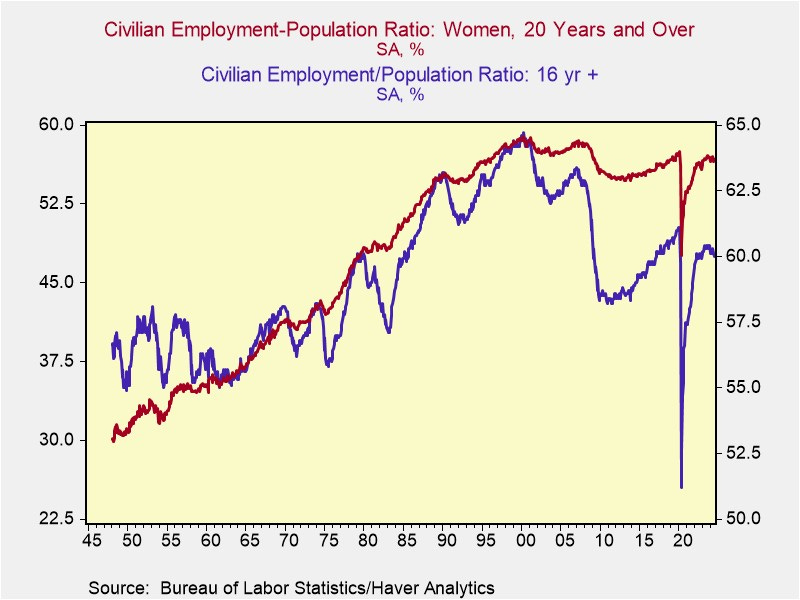

The demographic transition is underway in the US. Wealth effect from the pandemic and long Covid accelerated US workforce exits and pulled forward demographic/labor supply issues. We are still below the pre-Covid employment to population ratio even as female labor force participation has declined.

However, bad things become over the next 10 years with regards to the size of the US workforce, look at the projected further worsening in dependency ratios in 2060 in the first chart. US society really needs to act to stabilize dependency ratios by doing more to support working families — or we risk following the path of some Asian countries where population growth is in freefall.

While M-FAB readers may note that other economies have it worse, Americans are less healthy than Japanese and European counterparts. So even though we chronologically are “less old” than other advanced economies, many Americans’ biological age > than their chronological age. This, coupled with US social attitudes about spending vs savings and what retirement should look like, may imply both a reduced ability and desire to work. We are passed due for a national conversation.

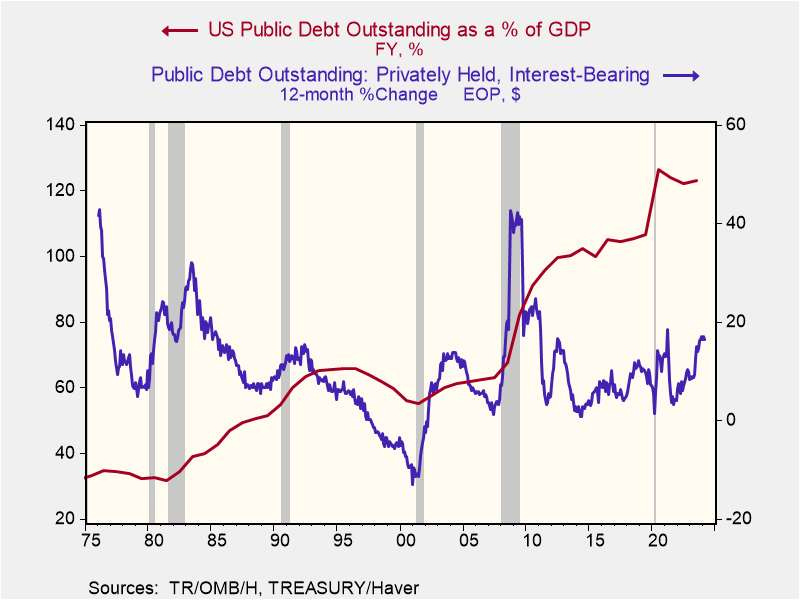

While by definition a government prints the money to fund its own budget deficit, at higher and higher levels of debt to GDP there are always economic and financial frictions in the deficit getting recycled back to fund the debt. These frictions, coupled with higher inflation and higher inflation expectations, drive up government financing costs and, over time, can be expected to crowd out corporate and household borrowers and slow economic growth.

Fifteen years of near zero interest rates, Social Security receipts funding other US borrowing and elevated Fed remittances to the Treasury from 2011-2022 due to QE which totaled roughly $1 trillion made the rise in US public sector indebtedness feel costless to US politicians. Let’s be honest, a number of Americans loved it.

The integration of China and eastern European countries into global economy were disinflationary and key to the fall in real interest rates and inflation. Aging demographics will push both savings and investment lower, but the risk is that elder cohorts globally to dissave more to fund consumption (including leisure and health care) and stay as long as possible in their homes, reducing housing affordability for working age families even as interest rates remain elevated. This table from Goodhart and Pradhan’s 2017 BIS paper which preceded their book nicely illustrates the emerging issue.

The breakdown of the 60/40 portfolio (60% equities/40% bonds) at higher levels of inflation (3%+) implies further increases in government financing costs as demand for long-dated government securities as current risk premia wanes. So the public sector debt burden is exploding, not costless anymore. With inflation and equilibrium interest rates higher rise; most asset values will fall over time. Financial stability events may occur.

Demographically, the world is in uncharted territory where we really do need to find a new set of economic policies. We are an economic environment characterized by strong consumption – particularly in the non-traded service sector (older people consume more services and fewer goods) – and a shrinking pool of US workers which, coupled with very high levels of fiscal stimulus, is why the labor market has remained resilient.

Retirees and (older) working Americans with wealth enjoy purchasing power even as younger working Americans find owning a home (see recent stats that median age of first time US home buyers is 40!), getting an education, affording healthcare and starting a family more and more costly and financially difficult. Wages have increased, but not kept up with prices of goods and services that the working age population needs to consume.

For this reason the incoming Trump Administration’s economic agenda understandably encompasses a search for new sources of economic growth and includes:

- Deregulation (presumably to enhance productivity)

- Smaller government (presumably to release workers to the private sector)

- Extension of 2017 tax cuts and maybe some new tax cuts

- Tariffs, which in the case of China, are likely to prove more permanent as a way of getting other countries to pay for tax cuts given to Americans

- Some deportations and more restrictive immigration policy to help support working class wages.

- Possible reform of healthcare (to anyone from the new Administration, please evaluate Uwe’s recommendations on how to fix it)

- Reliance on technology/AI to help solve demographic challenges

- Terming out the Treasury market (presumably to increase the potential for inflation to erode its value over time and help make government debt more sustainable).

But some of these policies may not be realistic.

We deregulate and believe we can unlock growth that is low cost. I do expect deregulation can contribute to US economic growth on net. However, in some sectors of the economy deregulation may also increase cost and contribute to inefficiencies.

A local example in Texas of how deregulation can increase costs and inefficiencies relates to the 2025 elimination of mandatory annual vehicle inspections in Texas. Vehicle inspections require among other things for drivers to prove 1) working lights, 2) active insurance and 3) sound brakes. A vehicle inspection in Texas costs $7. However, such inspections increase road and driver safety and I strongly suspect contribute to lower auto insurance premia for Texas drivers. My negative example aside – if done in a balanced and thoughtful manner (I can feel some readers rolling their eyes) deregulation could increase economic growth.